Greenbelts

#PoisionousGreenBelt

Written for a housing policy forum. Part 9

Also see: Housing – part 4: We are not short of land

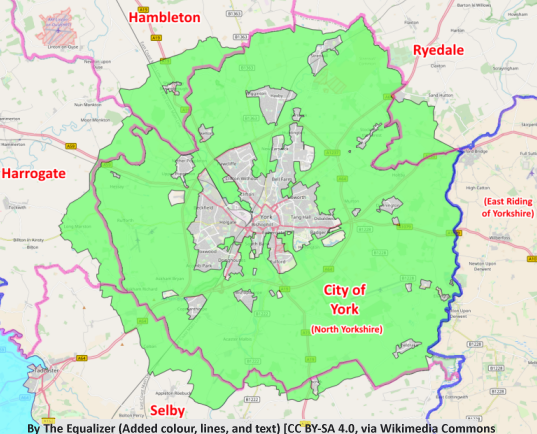

City of York ‘greenbelt’

Traditionally green belts were seen to stop urban sprawl and were the ‘green lungs’ of the city. This emphasised public health issues such as slum clearance. The policy is seen as a major instrument in terms of protecting the environment against environmental damage as a result of overdevelopment. It is a policy which is believed will to ‘protect the countryside’.

City parks very, very good. Green belts OK

The Barker Review of Land Use Planning, Interim Report – Analysis showed the value to the public (per hectare) of ‘city parks’ is over 60 times that of ‘urban fringe greenbelt’. (See Table 8.2.)

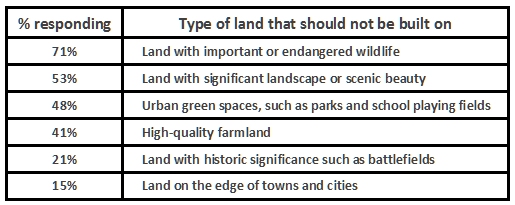

In the final Barker Review of Land Use Planning, a poll commissioned from Ipsos MORI asked ‘What types of land is it most important to protect from development?’. It allowed respondents three choices from six possibilities:

‘Land on the edge of towns and cities’ is green belt. It comes bottom of this list and gets less than a third of the votes given to ‘urban parks and playing fields’ – and the survey method – three votes for each respondent – blunted the earlier message that city parks were very much more valued than green belt land. However, Barker’s message is ‘City parks very, very good. Green belts OK’.

Corollary: Brownfield sites should become nature reserves and urban parks as with St Nicholas Fields, York or The Brickfields in Lower Halstow, Kent

But green belts are a cherished asset

The most prominent support for greenbelts comes from the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE), which say:

England’s 14 Green Belts cover more than a tenth (12.4%) of land in the country and, according to our research, provide a breath of fresh air for 30 million people. The ever-increasing pressure for more roads, housing and airport expansions means that it is vital to protect and invest in the Green Belts that we have….

The Green Belts are a cherished asset, as we have shown through the Our Green Belt campaign, and they’re also extremely valuable for food production, flood prevention, climate change mitigation and much more.

The Stroud News and Journal report a survey that the CPRE funded:

The poll on the 60th anniversary of the policy to protect land and countryside around towns and cities from development found that 64% believed existing green belt land in England should be retained and not built on while just 17% disagreed.

Why the contradiction?

There are enormous difference between the values attributed to greenbelts in the Barker Report – compared to those in CPRE surveys. The wording of the questionnaires almost certainly had an impact.The phrase Land on the edge of cities conjures up an image of a few fields next to urban sprawl, but the question Shall we preserve the green belt? evokes an image of wonderful sweeping green spaces. The CPRE trick is to make us associate wonderful green images with that farmer’s field next to the housing estate.

These images of rolling countryside garner support for greenbelt policies – even though many countryside views are outside the greenbelt: for example the inspiring view from Burham Downs towards Maidstone is not greenbelt. The other side of the River Medway, the tree lined roads around Luddlesdown are greenbelt. We might notice that Luddlesdown roads are too narrow for safe walking or cycling so are unlikely to provide a safe ‘breath of fresh air’ for ten million Londoners. Across the river, outside the greenbelt, these Londoners can find the Pilgrims’ Way Path along the North Downs and enjoy walking or cycling to Canterbury.

Greenbelts increase house prices

According to Zoopla, the houses inside the Luddledown area of green belt are three times as expensive as ones over the river, outside the greenbelt. Did this premium on house prices in greenbelt areas originate because wealthier people moved in or did the wealthy (and powerful?) ensure that their area was designated as greenbelt?

Paul Cheshire, Professor Emeritus of economic geography at LSE commented on the effects of the wealthy on the housing market in the Guardian:

Green belts are a handsome subsidy to ‘horseyculture’ and golf. Since our planning system prevents housing competing, land for golf courses stays very cheap. More of Surrey is now under golf courses – about 2.65% – than has houses on it.

Writing about National Parks, George Monbiot says:

[Are they] managed in the interests of the nation or for a tiny, privileged minority?

Could we say that about the greenbelts?

It’s the view

It’s easy to hide urban sprawl behind a belt of trees

In the Ipsos MORI survey for the Barker Report, two of the possible reasons for public support for greenbelts are ‘Land with significant landscape or scenic beauty’ and ‘High quality farmland’.

‘High quality farmland’ is a hat-tip to the increasingly important issue of food security, which will be discussed later – but greenbelts protecting food security may turn out to be as much of a myth as the protection of wildlife by greenbelt policy. Food security aside, the key support for greenbelts is driven by the feelings that caused the 53% response to ‘Land with significant landscape or scenic beauty’. This suggests images such as the National Parks, such as the North Yorks Moors or the Peak District. These are not part of any greenbelt.

In an experiment to understand the effect of ‘the view’ on people, Professor Richard Wiseman of the University of Hertfordshire, has constructed a large-scale multi-media space that aims to calm even the most stressed out of minds. He says:

Research suggests that the subdued green light enhances the production of dopamine in the brain and provide a calming sensation. In addition, the artificial blue sky helps create a mild form of sensory deprivation that will help them turn their attention inward and distract them away from daily stress.

In a context wider than an academic multimedia experience, my friend Sue walks ten miles a day to and from York, mostly along the footpath following the river. She says:

It’s obviously better to walk through greenery than housing but it’s not so good if it’s just fields. Walking through trees and woods is joyful and peaceful especially if there is the extra interest of rivers, streams, brooks and wildlife.

Sue’s journey by the river has not needed the protection of a greenbelt. Actually, despite the published maps, York has never actually had an official greenbelt. It hasn’t yet got an official local plan, as can be deduced from The ‘Local Plan’ on York Council’s website:

The full name of our Local Plan is ‘City of York Draft Local Plan Incorporating the 4th Set of Changes (April 2005)‘ – this and the associated appendices and proposals maps are the documents referenced when we make development control decisions (such as major developments in York, and planning permission).

The ‘Green Noose’

I am surprised how often I agree with publications from the Adam Smith Institute. Here are some (shortened) points made in the note, The Green Noose, by Tom Papworth in 2015:

- Green Belts are not the bucolic idylls some imagine them to be; indeed, more than a third of protected Green Belt land is devoted to intensive farming, which generates net environmental costs.

- The avenue of reform we favour is the complete abolition of the Green Belt, a step which could solve the housing crisis without the loss of any amenity or historical value.

- Failing this, we conclude that removing Green Belt designation from intensive agricultural land.

- In the short term, simply removing restrictions on land 10 minutes’ walk of a railway station would allow the development of 1 million more homes within the Green Belt surrounding London alone.

Read the Green Noose full report An analysis of Green Belts and proposals for reform.

Greening the greenbelt

In 2003 I wrote Greening the greenbelt. This made similar points to the Green Noose paper. Here is an extract:

The problem

Green belts are mechanisms for restricting the supply of planning permission. Green belt policy is usually regarded as the one strong weapon planners have against developers who would destroy our environment; our environment which is free for us all, rich and poor, to enjoy. But, in reality, it

— Increases in the value of land with planning permission

— Gives massive rewards to the affluent (owners of property and land)

— Penalises the poor and the young

— Rewards those that pollute the most – the affluent

— Protects green fields of monoculture with little biodiversity

Our suggestion

Open up the greenbelt to settlements that will

— Have dwellings and shops and public transport

— Use local horticulture – growing more food than conventional agriculture

— Cut food miles to 10% of the National average.

— Create more biodiversity than the farmer

— Have green footprints that are a quarter of the National average

Who just said “Dream on”?

Postscript 30th April 2018: Land, labour and food

A common argument in favour of greenbelt policy is that land is required for food production with a rising world population. However, Professor Cheshire’s horsey culture and golf courses on greenbelt land do not produce food. There is also the issue of food wastage and the destruction of food-value with the conversion of economically ‘inferior’ foods to ‘superior’ foods as discussed in Part 2. Part 6 also discussed the destructive effects of modern farming methods on medium term soil fertility.

Elizabeth and Paul Kaiser use no-till, labour intensive methods on their Singing Frogs Farm. Although the presentation below measures production in dollars rather than ‘food value’, it is inspiring to see how much food can be produced on a small amount of land with high levels of labour. This increases – without damaging soil fertility or the global environment:

Singing Frogs Far presents an example of a better way of food production, local food with local employment.

It’s difficult to find research which gives guidelines for the quantity of food that can be produced on small areas of land, when serious non-industrial efforts are made. In Food and permaculture, David Blume made the surprising claim that ‘Two acres produced enough food for 300 people’. He argues that the industrialised monocultures of modern farming use less labor. These have poor yields but are favoured by corporations:

The argument that we can’t produce enough ecologically is, at its source, promoted by corporations who benefit from a view of scarcity and limited resources which they control. Their constant cry is TINA “There Is No Alternative”. Right, and the wizard says, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!”.