Look, learn and improve

Written for a housing policy forum

Look, learn and improve

When Oscar Newman visited Leeds School of Architecture in 1976, I asked him how the students could go about designing better housing. I can’t give an exact quote but, as I remember, he said to look for the best housing you can find and design something 5% better. Basically: ‘look, learn and improve’.

I was shocked that an architect, who had proposed high profile theories of human interaction in housing should say something so lacking in theory: his book, Defensible Space; Crime Prevention Through Urban Design, makes predictions of how people interact depending on the architecture they live in. I had expected an answer involving spatial principles for the layout of housing and the connections between them: Principles on which designs could be constructed.

Computer algorithms to synthesise architectural form

‘Look, learn and improve’ was far from the theoretical approach of Christopher Alexander’s Notes on the synthesis of form, which was popular at the time. This aimed to develop a design methodology from basic theoretical concepts that could be used for generating architectural form using computer programs. In Computer applications in architecture: form generation, Dr Hatem El Shafie writes:

The third event was the start of laying the foundations for design methods: the view that design can be externalized and described. This view was fundamental to the use of computers in architectural design and was a direct or indirect effect of the publication of Christopher Alexander’s “Notes on Synthesis of Form” in 1964.

Generating designs from basic principles didn’t work at the time. Having tried myself, I wasn’t surprised.

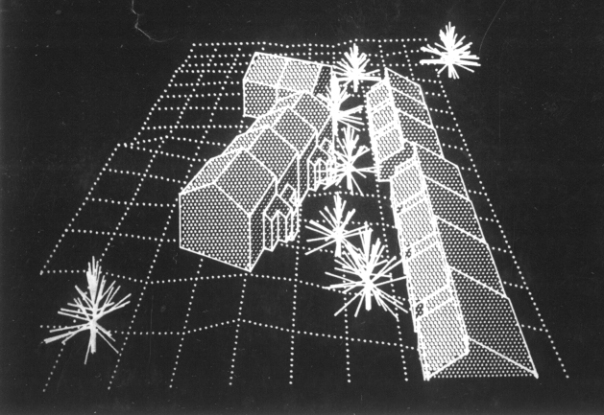

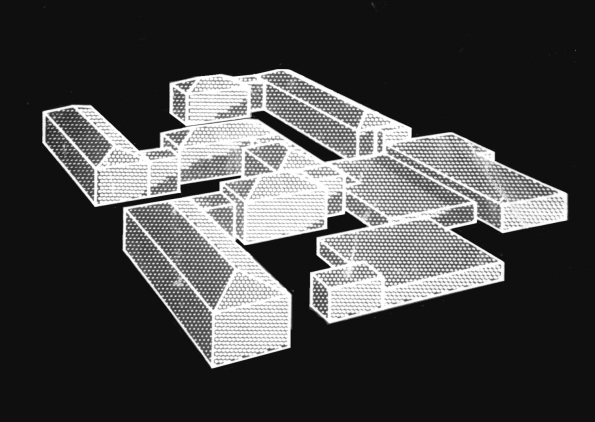

The computations I did at Leeds School of Architecture in the 1970’s took hours to complete but it wasn’t just computer power that stymied the attempt to synthesise architectural form suitable for practical buildings that could be used as offices or lived in: A few rules didn’t replace human intelligence. Several decades later, it remains to be seen if the new computer superbrains like IBM’s Watson or Google’s Deepmind can do better. I’m not holding my breath.

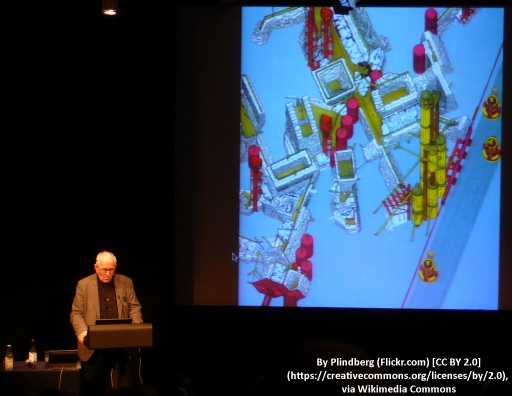

Archigram expanded minds

‘Look, learn and improve’ was also far from the mind expanding, innovative approach of the group Archigram, who advocated ‘nomadic alternatives to traditional ways of living, including wearable houses and walking cities—mobile, flexible, impermanent architecture that they hoped would be liberating’. Sir Peter Cook RA was one of the founders, seen here showing some of his work:

Archigram had an interest in cities – cities that people could live in – such as Peter Cook’s manifesto for a Plug-in City. This was a “megastructure” that incorporated residences, access routes, and essential services for the inhabitants. However, little, if any, housing has been built to the Archigram style – but there have been some impressive public buildings, like the Graz Art Museum by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier :

Referencing Archigram and brutalist housing blocks in Another One Bites The Dust: Robin Hood Gardens, Lloyd Alter wrote:

When I was in architecture school my favourite architects were the Archigram gang, but if you asked me about those who actually built things and were making real changes in the way things worked in the world, I would have pointed to Alison and Peter Smithson and Robin Hood Gardens. History has not been kind to them or their buildings, but it is still an icon and an inspiration.

Perhaps ‘the Archigram gang’ came out better than Alison and Peter Smithson because they didn’t do mass housing. The condemnation of Robin Hood Gardens was brutal. It was completed in 1972 with demolition starting in 2017 because it “fail[ed] as a place for human beings to live”:

Too theoretical, too glossy

I don’t know what Oscar Newman had in mind when he said ‘design something 5% better’ but neither Christopher Alexander’s Notes on the systhesis of form or Peter Cook’s Plug-in City followed Newman’s ‘look, learn and improve’ route (nor did the brutalist housing architects). The ‘innovative’ solutions may have been intellectually exciting, particularly to architects, perhaps the more so because they broke with the past.

Given their failures -in housing at east – it’s time to Look, learn and improve.