Housing – part 12: Friends, neighbours and architectural determinism

Written for a housing policy forum

Brutalist housing disasters

Brutalist buildings are typically massive sculptures, fortress-like, using exposed concrete construction – like the imposing and inpenetrable building of the National Theatre on London’s South Bank:

This Brutalist Movement influenced housebuilding, for example, the High Rise Flats in Oxgangs, Edinburgh. These were built in the early 1960s. In 2003, after years of campaigning by residents the council took the decision to demolish and redevelop them:

Much of the brutalist public housing built in the 1970s has been demolished. Their failure has even reached the main stream media, such as the story in The Express, Stop families being herded into high rise, crime ridden tower blocks:

A senior Tory today calls for an end to the “scandal” of “warehousing” families in tower blocks.

Andrew Boff, Conservative group leader at the Greater London Authority and the Tories’ housing spokesman, says children’s quality of life suffers in high rise housing and councils should put families in street-level homes.

“We need to be thinking about creating communities, not just building warehouses for families,” he said

The failures of large brutalist housing projects gave rise to renewed interest in theories about how architecture might determine behaviour. Architectural Determinism is a term used to describe these theories.

Architectural determinism

‘Archtectural determinism’ covers a range of beliefs about how architectural surroundings can change behaviour – and to what extent. In Building a better world: can architecture shape behaviour?, Jan Golembiewski gives several examples of the unrealistic claims made by some believers. He starts with:

Leon Battista Alberti, an Italian Renaissance-era architect, claimed in the 1400s that balanced classical forms would compel aggressive invaders to put down their arms and become civilians.

Golembiewski recounts some of the difficulties:

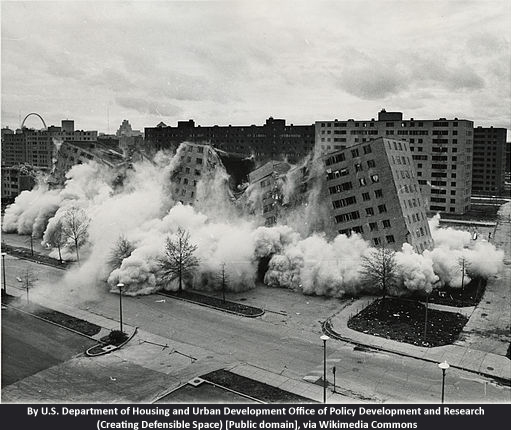

The high-point of [ the trend against Architectural Determinism ] was the delight shared over the demolition of the famously dangerous and dysfunctional Pruitt-Igoe urban housing complex in St Louis in the US.

It was designed by architects George Hellmuth, Minoru Yamasaki, and Joseph Leinweber to provide “community gathering spaces and safe, enclosed play yards.” By the 1960s, however, it was seen as a hotspot for crime and poverty and demolished in the 1970s.

As one friend checking this post pointed out: “Enclosed play yards” could create “hidden places for crime”. This was not a refutation of Architectural Determinism because it could be argued that the ‘architecture’ of enclosed play yards had ‘determined’ the level of crime.

Pruitt-Igoe’s demolition was big news:

Oscar Newman and Defensible Space

In contrast to the critics of Pruit Igoe, Oscar Newman, director of housing in New York, started his own brand of Architectural Determinism. In Defensible Space; Crime Prevention Through Urban Design, Oscar Newman outlined measures he had investigated – and implemented – for reducing crime in public housing. He advocated a clearly demarked hierarchy of spaces from ‘public’ through, ‘semi-public’ and ‘ semi-private’ to ‘private’. This heirarchy would encourage an increasing level of surveillance by residents going from public to private. This natural surveillance would inhibit antisocial behaviour and crime. The New York Times reported:

A three‐year study by a New York University research team [led by Oscar Newman] has produced dramatic evidence of a major cause of the terror that afflicts public housing residents in many major cities: The higher the building, the higher the crime rate.

The most dangerous type of public housing of all, the study found, is the high‐rise elevator building with floor upon floor of “double‐loaded Corridors” serving so many apartments, ranging along both sides of the hall, that residents can’t tell neighbors from strangers.

Newman’s ideas were taken up in the UK by Alice Coleman. In her book, Utopia on Trial, she gave the principles of Architectural Determinism a stronger emphasis than Newman’s. She allied herself with Margaret Thatcher who was enthusiastic about Coleman’s ideas.

Coleman believed poverty was no excuse for crime and that blocks of flats breed anti-social people. She actually said “These are the blocks that breed anti-social people.” Coleman’s views rather damaged Newman’s ideas by taking them to an extreme, which has engendered significant criticism – even from Newman himself.

In the mid 1970s Oscar Newman gave a talk at Leeds School of Architecture, where I worked.

A Pleasant Victorian Terraced Street … and design something 5% better

The week previous to Newman coming to Leeds, I had been on a coach trip with the architecture students to see some new back-to-back housing that had been built next to the University of York. (These were thought to be innovative because back-to-back houses had been banned as unhygenic in the early 20th Century. )

On the way back, I stopped the coach where I lived, in a street of small to medium sized terraced houses built in the 1870s. One side has short front gardens. The street was a friendly street, where our children played with neighbour’s children and we had street parties every year:

This street was vastly different to the high-rise flats in the Outgangs, Edinburgh. Did their children play in the street, like ours? Did they have street parties, like ours? Can they in Oscar Newman’s words “tell neighbors from strangers”? We could.

There was lack of interest in my Pleasant Victorian Terraced Street by the student architects. This prompted me to ask Oscar Newman how students should go about designing good housing. His answer “Go and find the best housing you can – then design something 5% better.” To me that meant designing something 5% better than my street.

I guessed he meant ‘better for the residents’. I Iiked this answer but I did worry that it would cut little ice with the students. I suspected that deep-down what impressed them and most architects was the visual impact of their designs – not how the residents in their schemes felt.

Leon Festinger and friendship patterns

Back in 1950, before Oscar Newman’s work, Leon Festinger had given a detailed description of architectural features which influenced how people would become friends. His study, Social Pressures in Informal Groups, was based on one particular housing scheme. He studied a housing community for married veterans of the Korean War, who were students at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He investigated the effect of housing layout upon friendship patterns, group formation, structure, and standards, and the process of communication. Much of the housing consisted of small, prefabricated single-family and detached homes, grouped around courtyards and facing away from access roads, similar to the layout of some of the prefab estates in the UK.

It found that friendships developed with neighbours, particularly those that were near or were easy to encounter for extra reasons – such as sharing the same post box. The effect of proximity and layout was the biggest determinant of friendships. Matching residents with similar attitudes and interests did not predicted friendships well. Chapter 9, A theory of group structure says:

People generally hesitate simply to introduce themselves to someone new. It is only after two people have seen each other several times that they will start to nod to each other from a distance and only after some time will it seem appropriate to communicate verbally. This passive kind of contact is probably in most instances the more important factor in determining whom one meets and consequently, to a large extent, with whom one makes friends.

Festinger’s book guided my family and I in choosing a house to live in: In 1972, we moved into a new co-operative housing development. Using Festinger’s ideas, we chose the house positioned near the intersection of two footpaths to make it easier to know our neighbours. It turned out to be a good choice. We found friendliness and neighbourliness there.

Later in the Pleasant Victorian Terraced Street we found friendliness and neighbourliness, partly fashioned by its layout. I again related this to Leo Festinger’s work.

Edward T Hall and personal space

In 1963, Edward T. Hall developed the concept of ‘personal space’. This is the region surrounding a person, which they regard as psychologically theirs. Most people value their personal space and feel discomfort, anger, or anxiety when their personal space is encroached. He identified four distinct zones: intimate space, personal space, social space, and public space.

In Why Do We Have Personal Space?, Natalie Wolchover explains:

The smallest zone, called “intimate space”, extends outward from our bodies 18 inches in every direction, and only family, pets and one’s closest friends may enter. A mere acquaintance hanging out in our intimate space gives us the heebie-jeebies. Next in size is the bubble Hall called “personal space,” extending from 1.5 feet to 4 feet away. Friends and acquaintances can comfortably occupy this zone, especially during informal conversations, but strangers are strictly forbidden. Extending from 4 to 12 feet away from us is social space, in which people feel comfortable conducting routine social interactions with new acquaintances or total strangers. Beyond that is public space, open to all.

In his book, The Hidden Dimension, Hall coined the term ‘proxemics’ for the study of personal space. According to Hall, proxemics is valuable in evaluating not only the way people interact with others in daily life, but also “the organization of space in [their] houses and buildings, and ultimately the layout of [their] towns”.

Festinger, Hall and Newman give insights of how people interact with each other in a spatial context and devlop their relationships but the importance of this differs: Some people want to make friends and close neighbours; others are not so bothered.

Who wants friends and neighbours?

Some depend on neighbours:

My grandma lived in a Victorian house in Bristol but had a holiday chalet by the sea.

Aged 90 she swam in the sea… she knew everyone. Her neighbours watched for her curtains to open in the morning and came knocking the day they remained closed.

I believe she died because she couldn’t face the loneliness and struggle she faced back in Bristol.

(Comment by Esther Dent Dodsworth)

Some aren’t bothered about neighbours:

I know more about the 668 ‘friends’ I have on Facebook than I do my neighbours.

(Daily Mail journalist)

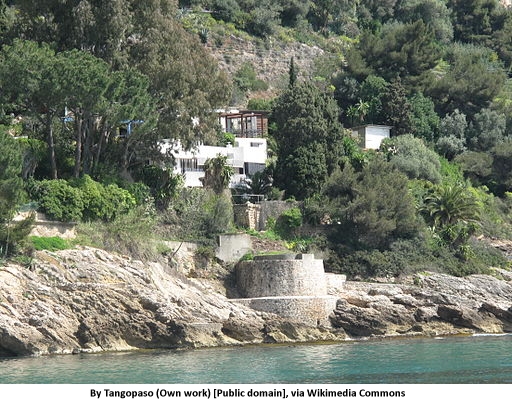

Eileen Gray’s house hid her from neighbours:

Some want to avoid ‘Neighbours from hell’:

They aren’t just the neighbours from hell, they are quite deliberately making your life a living hell. Maybe they’re shouting lewd comments when you leave the house, pumping up their music on purpose after you’ve told them you have an exam, or accidently-on-purpose throwing all their litter onto your lawn?

(themix.org)

Designing for neighbourliness and security

The layout and form of housing influences how people can get to know each other as Festinger and Newman have shown: They have shown this conclusively for their examples. Their examples were for specific groups: young student families studying at MIT and poorer urban New Yorkers. To these groups, neighbourliness and defensible space are important. To the Daily Mail journalist (I have more-friends-on-Facebook) or to someone with an elevated social status like Eileen Gray with a large well-defended house, these considerations are of much less importance.

In designing most housing schemes the ideas of Festinger, Newman and Hall are guides. It is still possible to use their insights and reject Alice Coleman’s extreme position “These are the blocks that breed anti-social people”, which leaves demolition as the only option. Even Newman thought that Coleman placed too much emphases on spatial aspects, sidelining other issues – such as the quality of management and maintenance of the buildings.

Inadequate management can ruin good housing. In 2003 Guardian Columnist Amielia Hill, in describing the decline of council housing, used the Manor estate in Sheffield as an example:

‘Twenty years ago, the Manor was considered the crème de la crème of housing estates,’ said Law. ‘Now you can walk round and take your pick of the empty houses, if you can crowbar off the boards from the windows. The council has let this area die.’

Failures of management have contributed to declines in many public housing schemes. This is not a refutation of the work of Festinger, Newman and Hall. It is a recognition that the configuration of the spaces we live in is just one factor in forming and maintaining human relationships.

Future posts will explore some novel approaches to management.