New economies for new estates

Car-free estates of prefabs with market gardens

Written for a housing policy forum – part 17

Improve these prefabs with modern cross-ply timber…

and add market gardens.

The previous post showed that estates of wooden prefabs with inbuilt market gardens, could provide cheap, green and neighbourly housing.

This post will suggest enhancements to the local economy that can help them become cheaper and greener.

A new Ministry of Works should be created and empowered to allow experiments in the design of housing estates. These should include new financial and legal mechanisms, such as local pollution taxes or subsidies to shops – where they also fulfill a social function.

In an entry for an ideas competition in 1976, Places fit to live and how to create them – RSPCA news – I made proposals for similar mechanisims:

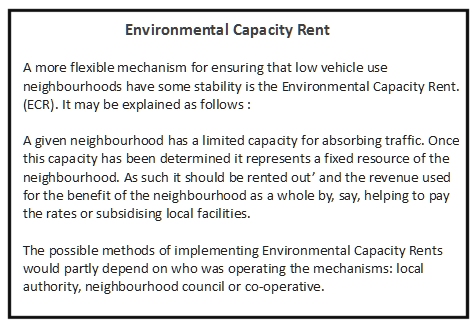

This competition entry proposed one particular mechanism, Environmental Capacity Rent, to be used where a small number of cars were allowed within settlements. It proposed a ‘cap and trade’ scheme similar to the EU emissions trading system (EU ETS) – as seen today – for carbon emissions: The proposal then was that the number of cars within a settlement should be capped:

Cap and trade systems like Environmental Capacity Rent should be of interest during the necessary modification of existing settlements (cities, towns, suburbs & etc.) to ensure that they pollute our environment less.

An important message is: Include financial and legal mechanisms as much a part of the design process as the plans of the building layouts.

Evaluating settlements

The proposed new Ministry of Works should commission prototypes to create a rich gene pool of settlement types so that the ones shown to work best can become part of our pattern book. There will be a need for criteria to judge ‘success’ but these are almost certain to change as projects progress. Here are some suggestions for parameters to be used in evaluating prototypes:

Number of residents

Density of settlement

Local cost of living

% of residents employed locally

% of food produced locally

% of goods bought from local retailers

% of goods made by local residents

Social class of the residents.

Weekly travel distances.

Energy and water use

Carbon footprints of residents

Protection of ecosystems

Happiness of residents

A measure of neighbourliness

These proposed housing settlements can be examined as separate local economies that trade with the outside and have a locally measured ‘GDP’.

Labour costs, degrowth and the Robot Revolution

Making basic household expenditure much lower (e.g. by cheaper housing and lower transport costs) means residents can afford to work less or have lower paid lower productivity work – fitting into our technological future.

Lower productivity is necessary to maintain full employment because degrowth, lower consumption and lower production, is necessary to save the environment for future generations. See Is green growth a fantasy? – and note the reply from the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs supporting degrowth:

“the reductions in demand that are required are severe in scale and we will not meet targets by tackling emissions intensity alone.”

Degrowth demands that settlement economies should have lower labour productivity – but, of course, this means pleasanter jobs. The link between productivity and wages means that labour costs must become lower. This can be achieved by using internal financial mechanisms – e.g. labour subsidies paid by carbon taxes – but this process requires a shift in intellectual values.

Apart from the degrowth absolutely necessary to avoid lethal climate change, there is another reason that the value of labour must fall: the Robot Revolution, where robots do much of the work humans have been used to doing.

This is not a new issue. In the 19th century Robert Owen predicted unemployment and a decline in the value of labour due to industrialisation:

If we can imagine a point at which all the necessaries and comforts of life shall be produced without human labour, are we to suppose that the human labourer is then to be dismissed to be told that he is now a useless encumbrance which they cannot afford to hire.

The aim for new experimental settlements is to slow the pace of life so it will be pleasant and the residents won’t be screwing the world’s climate as well as fitting into our destined and widely desired technological future. (Discussed in Climate change & the fallacy of the lump of labour fallacy.)

Lower internal labour costs will open up other opportunities: As one example, the cost advantage that wooden, factory built prefabs have over other climate friendly forms of buildings such as hempcrete or straw bale construction will narrow or be eliminated – processes that many argue have technical advantages over wooden prefabs.

These issues are surely too difficult to unravel using theoretical argument alone so an empirical, evidence-based approach is required to develop our ‘rich gene pool of settlement types so that the most successful can be chosen.

Creating a market

In a session this February on Clean Growth Strategy for the Parliamentary Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee, Lord Deben said:

It was George Osborne who allowed £7.6bn to be used to create a market and from that market the wind industry managed to buy new technology … to deliver what we have now.

Lord Deben noted that, following this stimulus, the market in wind power had delivered massive cost reductions to the cost of wind energy. This approach has similarities with the competitions for the design of the prefabs in the 1940s that the old Ministry of Works set up.

The proposals in these posts include the creation of a new Ministry of Works, which will stimulate the market with new cheap, green and friendly settlements. This range of new possibilities will include experiments for financial and legal mechanisms within future settlements.

What is the product in this market? The answer : whole settlements. Settlements that are green, cheap and neighbourly.

Starting in London?

There are existing policy initiatives that make London a promising place to start the cheap, green and neighbourly settlements.

The Need: Lower rents

London has an acute problem of housing. In Over 400,000 households in London spend more than half their income on housing, Laura Gardiner from the Resolution Foundation, said:

Typical incomes in London are higher than elsewhere in the UK but too often this extra income is dwarfed by the higher housing costs they face.

The scale of the capital’s housing crisis is such that around a million Londoners live in households where the majority of their income goes on housing costs.

Dealing with the cost of housing is a particular problem for renters,

The Land: Green belts

Siobhain McDonagh, MP for Mitcham & Morden, recently submitted Early Day Motion 1164, which proposes using some low-grade greenbelt land for housing:

the scattered plots of Green Belt land within a 45 minute travel time of London’s Zone 1 and less than a 10 minute walk to a train station to be ill-fitting to the purpose of the Green Belt; further recognises the important opportunity that this land offers with space for over 1 million new homes;

Siobhain’s campaign, a Labour MP, may be a politically do-able version of the arguments of neo-liberal organisations such as the Institute of Economic Affairs and Adam Smith Institute, who object to green belt policy as a burden on the poor.

Construction: Prefabs back in favour?

Prefabrication gains political favour again. In Designed, sealed, delivered, The contribution of offsite manufactured homes to solving London’s housing crisis, Nicky Gavron, chair of the London Assembly Planning Committee writes:

Loved or loathed, the ‘prefabs’ and system-built blocks of the past contributed significantly to supply. While the use of these technologies fell out of favour, London’s record since has been one of consistent failure to meet housing demand.

Today’s off site manufactured homes are characterised by their high quality, precision engineering, digital design and eco-efficient performance, truly twenty-first century homes. Construction within a factory environment achieves quality control that ensures fast builds and lengthy lifespans.

But we should remember Robert Hardiman’s Daily Mail article, which reported the battle residents had to try and save the Excalibur prefab estate in Catford that they loved:

But Excalibur is also a headache for the local council, a nose-thumbing contradiction of every rule in the modern Town Hall handbook.

And:

Yet, our history is here in these ingenious 20th century bungalows. They did not just provide homes fit for heroes. They have also put the high-rise arrogance of Britain’s modernists to shame.

In saying “Loved or loathed, the ‘prefabs’ and system-built blocks”, Does the London Assembly Planning Committee recognise that this really means:

Residents loved ‘prefabs’

Residents loathed system-built blocks

I hope so.

Car ownership: Low for poor, low near transport hubs

The Draft London Plan restricts, actually bans, provision for motorists near transport hubs. In Mayor plans bold new housing & infrastructure around cycling in London, London.gov says:

- Draft London Plan to require a doubling of cycling parking provision in many new developments

- New housing and offices near public transport links to be required to be car-free

- Parking provided will be required to support electric or ultra-low emission vehicles

- Mayor of London says it’s ‘essential’ London continues to reduce its reliance on car

Since Siobhain McDonagh’s campaign to build in parts of the greenbelt, concentrates around railway stations, application of policy is on the way towards these proposals for car-free estates of cheap, green wooden prefabs.

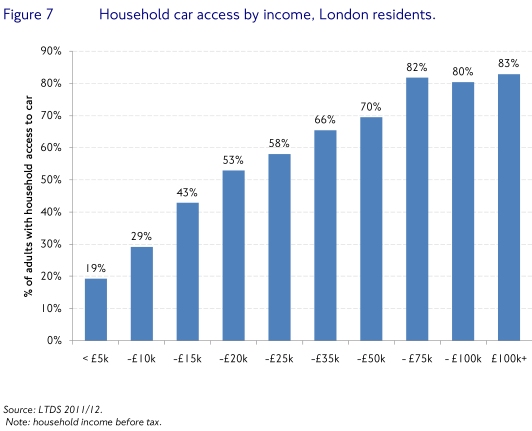

Statistics produced by the Road Task Force of Transport for London in Technical Note 12, show that a large proportion of poorer Londoners do not have household car access – about 20% of the very poorest but:

the general trend is for household car access to rise as household income increases, Figure 7 shows that car ownership rises steadily with income amongst households with incomes of up to £75k a year. Beyond this point, car ownership no longer rises with income, remaining at just over 80% on average.

Income aside, there are several London boroughs where ‘household car access’ is low. The lowest percentages are in denser, urban areas: City of London (13%), Islington (26%), Tower Hamlets (33%), Hackney (35%). In outer London suburban areas car access is high: Sutton (71%), Hillingdon (73%), Bexley (74%), Richmond upon Thames (75%).

Technical Note 12 summarises:

In total, 39 per cent of inner London households and 64 per cent of outer London households have access to a car.

Household access is higher in all outer London boroughs than any inner London borough, so that even the wealthiest inner London boroughs have lower car ownership than the most deprived outer London boroughs. Islington has the lowest level of car ownership, at 26 per cent, and Richmond upon Thames the highest at 75 per cent.

It also examines the rate of household car access in relation to access to public transport:

There is a strong relationship between household car access and access to public transport, with household car access rising as public transport accessibility falls.

There is also an additional relationship between inner and outer London, with household car access higher in outer than inner London at all public transport accessibility levels.

It is notable that those parts of inner London with the least good access to public transport have higher household car ownership than those areas of outer London with the best public transport access.

Summary: Areas with less wealthy residents with good public transport links have low car ownership.

London: A conclusion

Large sections of London’s population are lucky enough to live in areas with good public transport but have rents high enough to make life a struggle. Most will not have cars.

Siobhain McDonagh’s campaign is to build housing on low-grade greenbelt land, which is “within a 45 minute travel time of London’s Zone 1 and less than a 10 minute walk to a train station”.

Let some of these settlements be estates of cheap, green, wooden prefabs.

Postscript:The Hoo Peninsula Renewal City

In 2008, I made a proposal for a settlement on the Hoo Peninsular in Kent:

The Hoo Peninsula, which contains Kingsnorth [power station] is approximately 120 square kilometres, with a population of 25,000. This proposal is to use 50 square kilometres of this area to build a renewal city. It would have a population in excess of 250,000 people. The value of the associated planning permission will be in the order of £10 billion – planning permission for 100,000 dwellings at £100,000 per dwelling.

This proposal is that a significant proportion of the wealth generated by Hoo Renewal City should be set aside to fund full carbon capture at Kingsnorth. This would be a very large operation and the carbon capture technology is as yet in its infancy.

The proposals in Renewal Cities are different to those above, which are aimed at reducing the value of planning permission to the benefit of residents, for various reasons, such as avoiding instability in the housing market, there can be a case for the government capturing some of the development value. The Hoo Peninsular is interesting as a site for both possibilities.

There still is a railway line running though the peninsular which, if upgraded could get passengers to central London easily within the 45 minutes mentioned in Siobhain McDonagh’s Early Day Motion.

Postscript: A proposal for new plotlands development

A couple or years ago I suggested we look at plotlands development with the idea that ‘simple starter homes can be provided (with land and services) for less than £20,000’. It argued that a Sustainble Plotlands Association should be formed :

We propose that a fund be created to buy ‘plotland options’ on suitable sites. These would be legal options to buy land from landowners if planning permission were to be granted for plotland development. This would be for an agreed price or to an agreed price formula.

These might be attractive to some landowners because unless there is a strong political movement demanding cheap housing through plotland development the options cannot be exercised. If there is a successful political campaign (and starter homes become much cheaper) most of the windfall profit will be taken from planning permission anyway.

Contributors to the Sustainable Plotlands Association’s option will be eligible to take up one of the options held by the association. Rules for allocating (and possibly transferring) these need further consideration.

The postscripts show other aspects of developing housing that is a cheap, green and neighbourly. All matters for the consideration of a New Ministry of Works.